by Tim Dedopulos

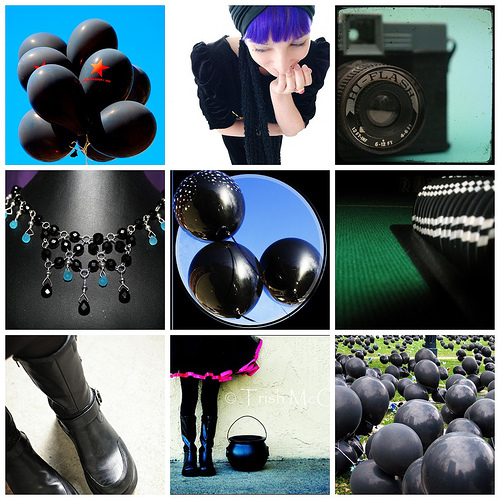

Technically the absence of light, rather than a colour itself, black is a complex symbol. In the western world, it carries a lot of negative connotations, many of them centred around fear and the unknown. This is not necessarily the case in other regions, although almost all cultures recognise the duality and opposition between black and white.

One common theory regarding black’s sinister associations is the obvious link to darkness and night-time. People are afraid of what the darkness hides; it is the time of thieves, nocturnal predators, malefactors and witches. If this is the main reason for black’s negative connotations, then perhaps the western world’s particularly strong negative feelings towards black can be explained in terms of European weather. Unlike the arid regions in the Middle East, Africa and large parts of Russia and China, European skies are commonly cloudy. Night time would have been genuinely pitch black, and therefore particularly intimidating. In countries where cloud cover was much less common, even moonless starlight provides a surprising amount of illumination, and night would have been much less blind. In other words, night just isn’t as dark in the tropics and equatorial regions as it is in cloudy temperate zones.

Technically the absence of light, rather than a colour itself, black is a complex symbol. In the western world, it carries a lot of negative connotations, many of them centred around fear and the unknown. This is not necessarily the case in other regions, although almost all cultures recognise the duality and opposition between black and white.

One common theory regarding black’s sinister associations is the obvious link to darkness and night-time. People are afraid of what the darkness hides; it is the time of thieves, nocturnal predators, malefactors and witches. If this is the main reason for black’s negative connotations, then perhaps the western world’s particularly strong negative feelings towards black can be explained in terms of European weather. Unlike the arid regions in the Middle East, Africa and large parts of Russia and China, European skies are commonly cloudy. Night time would have been genuinely pitch black, and therefore particularly intimidating. In countries where cloud cover was much less common, even moonless starlight provides a surprising amount of illumination, and night would have been much less blind. In other words, night just isn’t as dark in the tropics and equatorial regions as it is in cloudy temperate zones.

Another possibility commonly put forth is that in any given area, people with the power and wealth to not have to work outdoors at menial tasks are going to be paler in skin-tone than those who are exposed to the sun all day. That’s an inevitable biological fact. The implication then becomes that the rulers and aristocrats are going to be paler than their poorest subjects. Taken to its extremes, these differences become symbolised as an antagonism between black and white, with black indicating meniality and inferiority.

In the west though, black’s strongest associations are linked to the theme of evil. While these meanings may be retained to a certain outside the west, they tend to be significantly weaker. Backed up by religious imagery, black now symbolises tragedy, sadness, loss, despair, fear, discord, lies, bad things, malevolence, sin, satanic works and rituals, the netherworld and, by extension of the theme of loss, mourning and bereavement. For the Chinese, by contrast, black is the colour of the element of water, and conveys stillness and passivity rather than badness.

Western popular culture’s use of the colour has led to it being reclaimed, to an extent, by younger generations wishing to defy the orthodoxy, thumb their nose at authority, and generally irritate their parents. Accordingly, black now also symbolises a whole swathe of interpretations on the theme of defiance and freedom, such as rebellion, independence, mystery, occult power, sexuality, anonymity, acceptance and anger. Politically, it is generally associated with anarchism.

Even before its uptake by youth culture however, black retained a degree of respectability. It is a perennially fashionable colour for clothing – not only is it the most flattering and slimming colour to wear, it can also convey a degree of sophistication, elegance, seriousness and power. Authority figures have often used black to add weight to their influence – priests, judges, elite and/or secret police and so on – particularly where blue’s reassuring air of safety is not required. The difference between establishment and rebel, in this case, lies mainly in the style of clothing – but then, this year’s rebels tend to become next year’s authority anyway.

In the west though, black’s strongest associations are linked to the theme of evil. While these meanings may be retained to a certain outside the west, they tend to be significantly weaker. Backed up by religious imagery, black now symbolises tragedy, sadness, loss, despair, fear, discord, lies, bad things, malevolence, sin, satanic works and rituals, the netherworld and, by extension of the theme of loss, mourning and bereavement. For the Chinese, by contrast, black is the colour of the element of water, and conveys stillness and passivity rather than badness.

Western popular culture’s use of the colour has led to it being reclaimed, to an extent, by younger generations wishing to defy the orthodoxy, thumb their nose at authority, and generally irritate their parents. Accordingly, black now also symbolises a whole swathe of interpretations on the theme of defiance and freedom, such as rebellion, independence, mystery, occult power, sexuality, anonymity, acceptance and anger. Politically, it is generally associated with anarchism.

Even before its uptake by youth culture however, black retained a degree of respectability. It is a perennially fashionable colour for clothing – not only is it the most flattering and slimming colour to wear, it can also convey a degree of sophistication, elegance, seriousness and power. Authority figures have often used black to add weight to their influence – priests, judges, elite and/or secret police and so on – particularly where blue’s reassuring air of safety is not required. The difference between establishment and rebel, in this case, lies mainly in the style of clothing – but then, this year’s rebels tend to become next year’s authority anyway.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed